There is a lot of buzz in commercial circles concerning the new environmental sustainability regulatory reporting requirements that are set to become effective in January 2024. The latest changes are the next step forward in the EU’s efforts to honour the commitments made as a signatory to the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement.

Why Were New Reporting Requirements Needed?

The EU’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (EU-CSRD) builds on the framework that was put in place with its predecessor, the Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD), which was adopted in 2014. Both regulatory schemes focus on the sustainability practices and environmental impact of the individual businesses that produce and distribute goods and services for consumers.

The directives are intended to increase transparency and accountability across the entire business chain, making it easier to identify and address gaps and loopholes in existing corrective measures.

Klaus Schwab, founder of the World Economic Forum, aptly puts it:

“Creating long-term value requires both a focus on financial and sustainability performance. This means we need tools for measuring sustainability performance just as we have for financial performance.”

Essentially, businesses are required to provide detailed reports detailing the social and environmental impact of their day-to-day operations. The global nature of many businesses in the EU has presented a particularly challenging hurdle for regulatory agencies to grapple with. In most instances, the production of goods sold by one business is likely to involve the production of goods and services created and distributed by multiple other businesses located around the globe. Each step in the chain of production creates its own impact, or “footprint.” The new regulations represent an attempt to gain a better understanding of how each party is contributing to the whole.

The Challenges the EU-CSRD is Intended to Address

To date, progress in achieving the goals outlined in the 2015 Paris Agreement has been hampered by a series of persistent and formidable challenges. The necessary changes that would help to ensure a sustainable future for all require significant changes that cut across several entrenched and powerful sectors of the global economy. Understandably, not everyone is enthusiastic about the shift of favour from one industry to competing alternatives. This has resulted in intense lobbying, legal challenges, and spirited political debate attempting to muddy the waters of what sort of activity could be classified as sustainable and thus continue to receive stakeholder funding.

It became apparent that the early reporting requirements lacked clarity and enforceability, contributing to the overall confusion and creating gaps that were often used as a means to legally kick the proverbial can down the road. The EU-CSRD is intended to correct the noted issues.

What’s Changing in 2024?

A panel of high-level experts commissioned by The European Court of Auditors to report on the challenges of creating a more sustainable financial system concluded:

“The challenge is how to organise and finance a socially just and environmentally sustainable transition towards a climate-neutral and resilient economy. It is widely agreed that this transition will require significant public and private investment. This will require both raising finance for the investments needed to achieve a carbon-neutral economy and strengthening financial stability by incorporating environmental, social, and governance (ESG) considerations into business and investment decisions.”

The categorization and mapping of all industry actions and their impact on society and the environment was always an ambitious goal, to be sure. It has understandably presented many logistics challenges to be overcome as we move forward. These challenges have been further complicated by resistance from industry and political spheres concerned with the potential loss of future profitability if their business practices are not aligned with current or future sustainability standards.

The NFRD represented this early stage of the EU Taxonomy Regulation project. Now, with years of experience under their belt, the responsible agencies have a better understanding of where more clarity and stronger standards are needed to ensure the effectiveness of the regulatory efforts is not being undermined by those who would benefit from maintaining the status quo. The EU-CSRD will help to shore up the initial documented weaknesses in the NFRD that have surfaced since its implementation.

Here are some of the most notable changes that will impact what and how businesses must report under the new EU-CSRD:

- A new double materiality requirement means companies must now report on both the impact that their activities have on society and the environment and the risk that the company faces from environmental and regulatory change.

- Reports must include the impact of the company’s operations as well as the operations of the various companies at every stage of their supply chain.

- Adherence to a new standardised reporting format in accordance with the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) and the EU Taxonomy

- Mandatory external verification requirements.

- Independent third-party audits to increase accountability and close loopholes.

Much of the current angst is related to the upcoming expansion of who will be required to report their activities under the EU-CSRD. The NFRD limited reporting requirements to only those companies with 500 or more employees. This equated to around 11,700 companies that were required to submit reports.

Beginning in January 2024, the EU-CSRD will commence the first of a series of annual expansions aimed at spreading the reach of the reporting requirements across all businesses. The first expansion will pull in EU companies, or companies listed in the EU market, that meet at least two of the following criteria:

- 250 or more employees

- A balance sheet of €20 million or more

- €40 million or more in net turnover

It is important to note that this is the most basic classification. The EU-CSRD includes several caveats and lists of extenuating circumstances that have the potential to catch up with a much greater number of businesses in the net of responsibility than may initially fall under these baseline criteria.

This is also merely the first of several planned expansions with the ultimate goal of making a complete transition from the current economic system to one that is completely sustainable and inclusive. Achieving this stated goal will require that all businesses eventually come into compliance with the new reporting standards.

As it stands, the newest reporting requirements are expected to impact at least 50,000 businesses. Experts caution that the number of impacted businesses may be much larger, as businesses upstream and downstream of the EU companies may have an obligation to report as well.

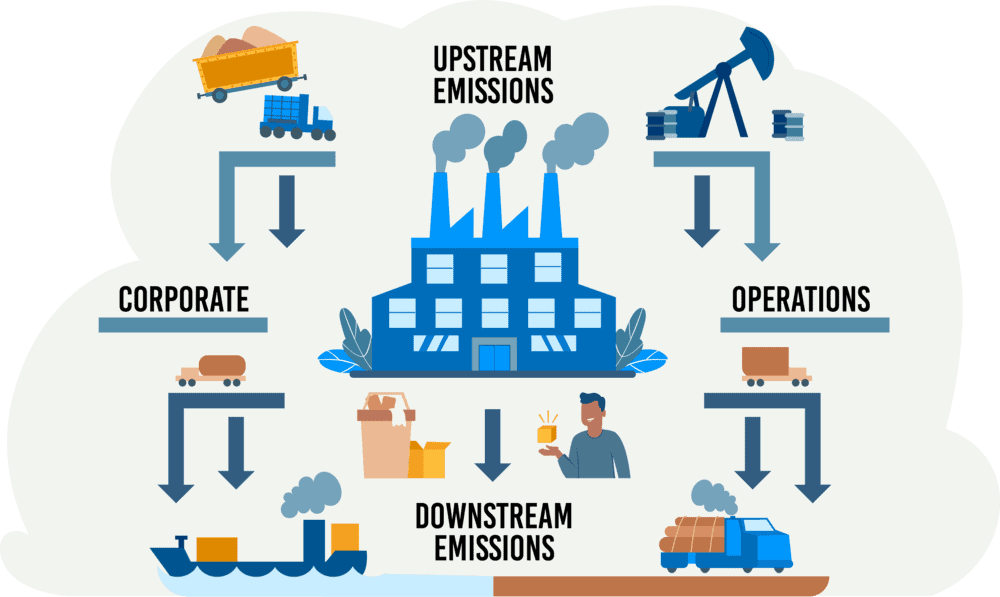

Let’s take a closer look at the role that downstream and upstream activities play in the bigger accountability picture through the lens of the most commonly used accounting tool, the Greenhouse Gas Protocol (GHG Protocol).

The Greenhouse Gas Protocol

The EU-CSRD uses the Greenhouse Gas Protocol, the most widely accepted model for assessing an activity’s impact on the environment. The GHG Protocol looks at the emissions produced across three distinct areas or scopes of activity.

Scope #1

Scope #1 encompasses the GHG emissions for which the company itself is the immediate source. This could be direct emissions produced by the company’s own factory or manufacturing facility or emissions produced by delivery vehicles and employee fleet vehicles owned and operated by the company and its employees.

Scope #2

Scope #2 covers the secondary emissions impact that results from a company’s consumption of an emission-producing element. An example of a scope #2 emissions event might be the emissions generated to produce the energy required to meet the high consumption demands of the new artificial intelligence large language processing models.

Scope #3

Scope #3 covers all of the indirect emissions activities that are incurred by organisations and individuals that make up the original company’s supply chain or value chain. Companies today are less likely to be the sole producers of their goods or services. Instead, most companies will rely on an array of different partners, with each partner producing one or more components of the original company’s product. These partner companies will, in turn, rely on their own network of suppliers and so on.

Scope #3 also takes into account the emissions produced in transporting the company’s goods or services to the consumer and the emissions produced through the consumer’s use and eventual disposal of the product.

Scope #1 and Scope #2 are fairly straightforward and fairly simple to calculate. However, the simplicity of the first two scopes is due in large part to the overwhelming complexity of the third scope. For many companies operating in the EU and around the world, Scope #3 could easily account for as much as 90% of their entire emissions output totals. This makes wrangling with Scope #3 reporting a challenge in and of itself.

To provide a better framework for scope #3, the category has been further divided into upstream and downstream activities. So, let’s look at how these two classifications fit into the bigger picture.

Upstream Emissions

Upstream emissions are the emissions that occur during the production of your goods. These could be the direct emissions produced by a supplier in creating a component for a company’s product, or they could be the indirect emissions produced by a supplier’s own partner companies. Upstream emissions can be incurred at any point in a company’s supply chain as a result of the processing, extraction, transport, or creation of any materials or components used in the end product.

Downstream Emissions

On the flip side of the equation, downstream emissions are those that are emitted through the lifetime use and disposal of a company’s product or service. The most obvious examples of downstream emissions are those produced by auto manufacturers. This would include the emissions produced by a single automobile through standard use by a consumer over the course of its expected lifespan.

Downstream emissions also include any emissions related to the disposal of the product at the end of its usable lifespan and factor in the potential recyclability or alternative uses for a product or service and the length of its usable lifespan before it must be disposed of and replaced. Examples of end–of–life downstream emissions considerations might include the destruction and processing of the various parts of automobiles and the dismantling of ships.

How Do Downstream and Upstream Emissions Factor into EU-CSRD Reporting?

There is a lot of uncertainty regarding the impact that the new upstream and downstream emissions reporting requirements included in the EU-CSRD will have on businesses. Here are a few of the hurdles that business owners are reporting as they attempt to ensure that they comply with the new EU-CSRD requirements.

Lack of Access to Upstream Emissions Data

The immediate concern is largely related to the initial confusion that is resulting from a lack of clarity over who is required to report under the new regulations. Larger companies with widespread supply chains are concerned about a lack of access to the necessary data to report the emissions impact of suppliers who exist further down the supply chain and are not under the supervision of, or in some cases, have no direct relationship with, the reporting company itself.

These concerns may be largely unwarranted. The EU is aware that the new reporting requirements represent a seismic shift in the status quo of business finance and partnerships. With this in mind, they have built a 3-year grace period during which businesses are required to submit all known data and documentation of their due diligence attempts to obtain any unknown data. The scope and nature of the EU’s classification system mean that some turbulence is going to be unavoidable at the outset. However, as reporting requirements have become the norm across all businesses and the system becomes populated with data, the ability to cross-reference entries in the database should make the reporting process much easier for everyone.

Outsized Impact of Downstream Emissions

Another common concern centres on the potentially negative impact that excessive downstream emissions reports might have on the company. Many business owners consider these emissions to be beyond their immediate control and question the fairness of having to account for their impact when considering the overall sustainability of their company.

This is a complex problem. However, it is important to remember that creating a safe and habitable planet for all is the driving goal behind these requirements. When viewed from that perspective, it is clear that the impact that a report may have on business viability cannot take precedence over the impact that emissions are having on the environment. That being said, this is a very real concern for otherwise sustainable companies. Fortunately, there are multiple factors that go into determining a company’s overall sustainability. For example, products that contain components that are commonly salvaged to be repurposed for other uses may offset some of the downstream emissions impacts if there is sufficient proof or widespread reuse efforts. Of course, the emissions of these secondary recycling operations must be factored into the totals as well.

The EU is sensitive to the reality that excessive downstream emissions are one of the more sizable hurdles hampering a few otherwise “green” products. One of the clearest examples of this conundrum are the lithium batteries that power most electric vehicles. On the one hand, electric vehicles eliminate the emissions that would have been produced by a gasoline-powered vehicle. This should put electric vehicle makers safely in the sustainable industry category. However, the need to factor in the high upstream and downstream emissions produced in the sourcing of raw materials, production, and eventual disposal of lithium batteries is proving problematic, as the excessive emissions impact at each of these stages is erasing a large portion of the gains achieved during the usable lifespan of the battery.

Utilities and other industries using nuclear power as a cleaner source of sustainable energy face a similar challenge when they must incorporate the hefty impact of the disposal of nuclear waste products.

When viewed through the lens of an electric vehicle manufacturer, it is easy to see the new EU-CSRD as putting roadblocks in the path of industries that are striving to produce more sustainable products. If you pan out and look at the broader picture through the eyes of the global community that depends on a habitable planet, it is easier to understand the reason behind these requirements.

The lithium battery is problematic, but it served to advance the industry through the earliest production, allowing electric vehicles to gain a foothold in the market, which in turn opened up funding for forward-looking companies to put their best minds to work imagining safer, more sustainable alternatives. This is precisely what regulation is intended to accomplish. Stringent reporting requirements make it easy to quickly spot problem areas in otherwise viable industries. Holding industries and companies accountable incentivizes innovation and encourages them to strive for better solutions, which ultimately benefits everyone.

Conclusion

The upcoming environmental sustainability regulatory reporting requirements, embodied in the EU-CSRD, effective January 2024, mark a significant step in the EU’s commitment to the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement. The directive addresses the need for increased transparency and accountability in businesses’ sustainability practices, building upon the framework of the NFRD. Despite challenges, the EU-CSRD aims to rectify early reporting issues and expand its scope annually, with notable changes including a double materiality requirement, standardised reporting formats, and external verification mandates. The focus on downstream and upstream emissions, assessed through the Greenhouse Gas Protocol, introduces complexities, particularly concerning data access and concerns about downstream emissions’ impact on business viability. However, the EU acknowledges these challenges, providing a grace period and emphasising the broader goal of creating a sustainable future. The regulations, though posing hurdles, are crucial for holding industries accountable, encouraging innovation, and fostering a global commitment to environmental well-being.